A Clinician's Guide to the Collapsed Labyrinth: Unpacking Vestibular Atelectasis

Even after decades in this field, you can still come across a new concept that changes how you think. That happened recently when I saw the team at VestibularFirst propose a discussion on Vestibular Atelectasis. It was a term I had never encountered, and it prompted me to dive into the latest research.

What I found helps explain some of our most complex patients—the ones who defy a simple diagnosis. They present with a history that points toward a severe unilateral vestibular loss, but their symptoms have confounding features that don't quite fit the typical clinical picture. A recent and insightful paper published in Audiology Research helps us connect these dots. The article, 'Vestibular Atelectasis: A Narrative Review and Our Experience', by Tozzi and colleagues, provides an in-depth examination of this rare but critical diagnosis.

What Is Vestibular Atelectasis? A Deeper Look

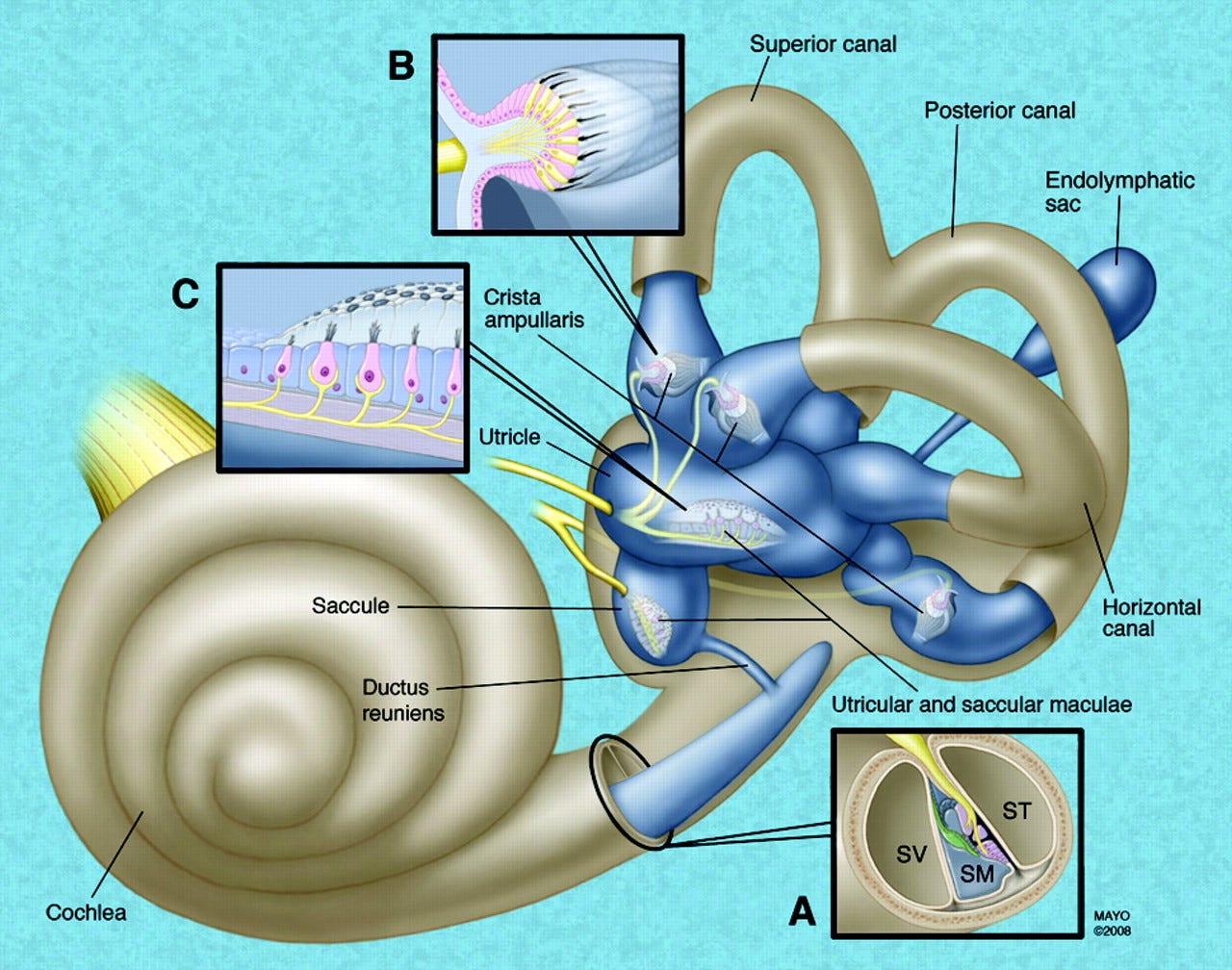

At its core, Vestibular Atelectasis (VA) is the physical collapse of the membranous labyrinth. Think of pulmonary atelectasis, where a lung collapses and can no longer exchange air. In VA, the collapsed inner ear structures can no longer properly sense head motion, leading to a profound vestibular hypofunction.

This collapse isn't random; it's often the result of another disease process:

Endolymphatic Hydrops: In conditions like Meniere's Disease, the inner ear swells with excess endolymph fluid. This sustained pressure can cause the delicate membranes to rupture and subsequently collapse.

Blood-Labyrinth Barrier (BLB) Impairment: Think of the BLB as a strict gatekeeper for the inner ear fluids. If this barrier becomes ‘leaky’ due to inflammation or vascular issues, proteins and other substances can seep into the perilymph, changing the fluid dynamics and potentially leading to membrane collapse.

Direct Trauma: A significant concussion or a temporal bone fracture can cause direct physical damage to the labyrinth, resulting in a traumatic collapse.

The Paradoxical Clinical Picture

What makes VA so tricky is that it mimics many other vestibular disorders. A patient with VA will show the classic signs of a unilateral vestibular loss (UVL), such as a positive head impulse test and significant balance deficits.

However, they will also present with paradoxical signs that seem to contradict a state of hypofunction, explained by theories like the 'third window' effect (where an abnormal third window in the inner ear can lead to unexpected symptoms) and the 'floating labyrinth' (where the inner ear structures are not in their usual position, leading to unusual symptoms).

The Diagnostic Process: From Bedside to Advanced Imaging

Identifying VA requires sharp clinical reasoning. A clinician can raise suspicion through a bedside exam that confirms a UVL (e.g., HIT) while also finding paradoxical signs (e.g., Tullio/Hennebert signs, persistent positional nystagmus). Advanced testing like vHIT, VEMPs, and MRI with Delayed FLAIR helps confirm the diagnosis by revealing the pattern of loss and the physical state of the labyrinth.

PT Management: Retraining the Brain Through Neuroplasticity

Since VA is an irreversible structural failure, physical therapy does not heal the ear. Instead, our goal is to leverage neuroplasticity to retrain the brain to compensate for the missing information. This is a highly active process centered on three key areas.

1. Gaze Stability (VOR Adaptation)

The primary goal is to reduce retinal slip and eliminate the patient's sense of oscillopsia (bouncing vision) during head movements. We achieve this by inducing adaptation of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR).

Precise Exercises: Treatment starts with VOR x1 viewing, where the patient maintains focus on a stationary target while moving their head at increasing speeds, for up to two minutes. We then progress to more complex tasks like VOR x2 viewing (head and target moving in opposite directions) and performing these exercises while standing on unstable surfaces (e.g., foam pads) to add a balance challenge.

2. Sensory Reweighting (VSR & VCR Adaptation)

This is the core of long-term functional recovery. We must train the brain to change its balance algorithm fundamentally. It needs to learn to down-weight the now-unreliable vestibular signals and place a higher 'weight' or reliance on visual and somatosensory inputs to drive the Vestibulo-Spinal (VSR, which controls balance during movement) and Vestibulo-Collic (VCR, which controls head and neck movements in response to balance changes) reflexes.

Precise Exercises for VSR: We systematically manipulate sensory conditions to force this reweighting. This involves progressing through static and dynamic balance activities, such as:

Static Posture: Performing standard CTSIB or SOT is likely to identify C4 and similar C5/C6 Dysfunction Patterns.

Dynamic Gait: Walking with horizontal and vertical head turns, tandem walking, walking backwards, and navigating ramps or uneven terrain. These tasks force the VSR to adapt and produce stabilizing motor outputs during real-world movement.

3. Habituation (Symptom Management)

While sensory reweighting rebuilds the core balance strategy, habituation serves as a targeted tool to reduce any remaining, specific sensitivities. It is a desensitization process, not a functional rebuild. For instance, if a patient has reasonable postural control but still reports a burst of dizziness with a specific movement, like bending over to tie their shoes or making a quick turn in a busy aisle, habituation can be applied.

Precise Application: We use this if a patient has reasonable postural control but still reports a burst of dizziness with a specific movement, like bending over to tie their shoes or making a quick turn in a busy aisle. We prescribe repeated, controlled exposure to that exact stimulus (e.g., five repetitions, twice daily) until the brain's defensive response is diminished.

By precisely targeting these three areas, we can guide the brain through the process of central compensation, allowing patients with VA to achieve a remarkable level of functional recovery.

Brian K. Werner, PT, MPT, is a physical therapist who has specialized in treating patients with vestibular and balance disorders for over a quarter of a century. As the National Director of Vestibular Education and Training for FYZICAL Therapy and Balance Centers, he has dedicated his career to advancing the field and improving patient outcomes. You can find more of his insights and educational content on his Substack.