Beyond the Basics: Why the mCTSIB Fails as a Definitive Vestibular Tool

Consider this common scenario: a 62-year-old male presents with persistent unsteadiness. He reports dizziness on unstable surfaces when moving his head and looking up—classic signs of vestibular dysfunction that point toward a dynamic, multi-faceted problem. You need answers, so you turn to the balance testing you learned in school: the Modified Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction on Balance (mCTSIB).

But you face a profound problem. The results come back but fail to reflect the deficits this patient describes. Why? Because the mCTSIB lacks the fundamental tools to assess the dynamic challenges at the heart of his complaint. While many clinicians use the mCTSIB as a quick screen, a dangerous trend has emerged: using its limited findings to drive clinical decision-making. This is a profound mistake.

We must restate this notion: The mCTSIB is not a valuable test for comprehensively assessing patients with dizziness and balance disorders.

Using it as a primary driver for treatment constitutes a clinical error.

This does not mean the foundational concepts of sensory integration testing are without value; they are the bedrock of our understanding. However, we must recognize that the mCTSIB—and, as we will discuss in a future article, the standard CTSIB—do not suffice in isolation. Acknowledging their flaws marks the first step toward a more effective clinical paradigm.

Deconstructing the Misleading Data

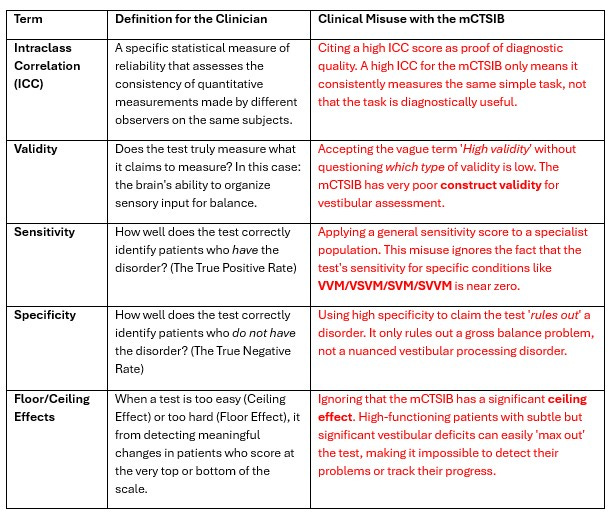

Proponents of the mCTSIB often rest their arguments on what appears to be strong psychometric data. Before we dissect the specific numbers, we must establish clear definitions for these terms and how clinicians often misuse them.

Stop the Substack if listening and review the table.

The Foundational Flaw: The Absence of Sensory Conflict

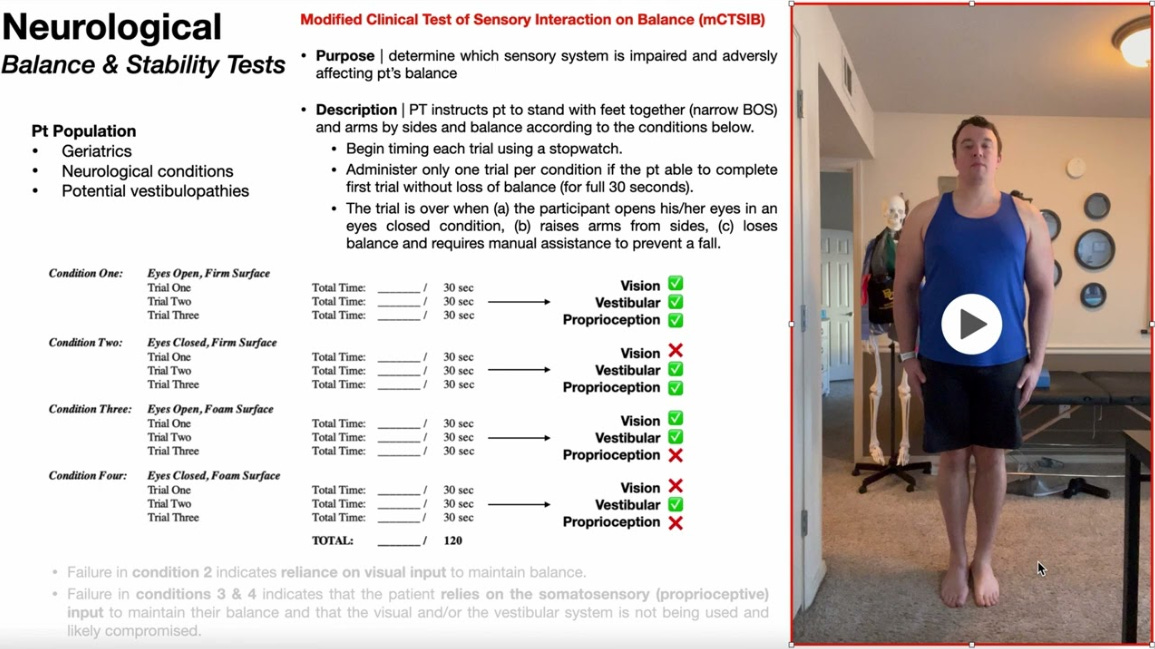

Let's be direct: a test that cannot provoke the pathology it purports to assess is invalid. To understand why the mCTSIB fails, we must first examine what its four conditions aim to determine:

Eyes Open, Firm Surface: A baseline test using all sensory systems (vision, somatosensory, vestibular).

Eyes Closed, Firm Surface: Removes vision, theoretically testing somatosensory dominance.

Eyes Open, Compliant Surface: Distorts somatosensory input, theoretically testing visual dominance.

Eyes Closed, Compliant Surface: Removes vision and distorts somatosensation, theoretically isolating the vestibular system.

This theoretical breakdown is overly simplistic and clinically misleading. The reality of the 'eyes closed' condition serves as a prime example. For some highly vision-sensitive patients, closing their eyes improves their stability by removing a conflicting sensory cue. For others, it makes them significantly worse. You cannot differentiate these opposing patient profiles without actual visual conflict conditions.

This leads us to the mCTSIB's fatal flaw: Omitting Conditions 3 and 6 from the original Sensory Organization Test (SOT). The designers did not include these conditions arbitrarily. They designed them to create a powerful visual conflict using an optical flow that produces a torque-like effect on the visual system. This stimulation is crucial because it induces sway and provokes symptoms in visually dependent patients, allowing us to observe their inability to suppress inaccurate visual information directly. The test designers left this critical component out of the mCTSIB partly because the original foam dome used in the standard CTSIB was largely ineffective at inducing this necessary visual torque. The mCTSIB threw the baby out with the bathwater by omitting it entirely instead of improving it.

This omission creates critical consequences:

It Cannot Identify Visual Dependency: A patient with a clear VVM who over-relies on vision can easily pass the mCTSIB. Without a visual conflict condition, you cannot expose their inability to function when their vision is inaccurate. This critical diagnostic error leads to ineffective treatment.

It Masks Underlying Sensory Mismatch: The test's four simple conditions do not provide enough data to differentiate between a Somatosensory-Vestibular Mismatch (SVM), a Visual-Vestibular Mismatch (VVM), or other complex patterns. The test only tells you that balance is worse on a compliant surface or with eyes closed—a rudimentary finding that provides no specific direction for targeted neurorehabilitation.

It Lacks Predictive Validity for Treatment: Because the mCTSIB fails to identify the particular nature of the sensory weighting problem, it cannot predict which treatment will be effective. Does the patient need to learn to suppress visual input? Do they need to enhance vestibular gain? The mCTSIB leaves you guessing. Basing a treatment plan on a guess does not meet the standard of care our patients deserve.

It Creates False Confidence and Invalidates the Patient Experience: The mCTSIB's simplicity is its most excellent trap. It gives the clinician an objective finding (e.g., 'timed out on condition 4') without providing any real diagnostic insight. This creates a false sense of confidence and leads to generic treatment plans that target the finding (poor balance on foam) instead of the cause (e.g., an inability to resolve visual-vestibular conflict). A 'normal' or inconclusive mCTSIB result is profoundly invalidating for the patient in our vignette. It fails to capture the dynamic nature of their dizziness, potentially leading them to believe the problem is not real or that the clinician does not understand it.

The Clinical Imperative

Using the mCTSIB as anything more than a cursory screen means accepting diagnostic ambiguity. For the vestibular specialist, ambiguity is the enemy; it leads to generic, non-specific exercises that fail to address the patient's core neurological deficit.

The mCTSIB has a place, but that place is limited. It can tell you a fire exists. It cannot, however, tell you the fuel source or where to point the hose. For vestibular professionals, whose job it is to be expert firefighters of the sensory system, that is a flaw we cannot ignore. We must demand more from our tools to deliver the precision care our patients expect and deserve.