'Partial' Progress: A Critical Call for Precision in Balance Stance Terminology

Let's begin with what we know with absolute certainty. In the realm of balance assessment, two stances reign supreme, their roots tracing back to the very foundations of neurological examination:

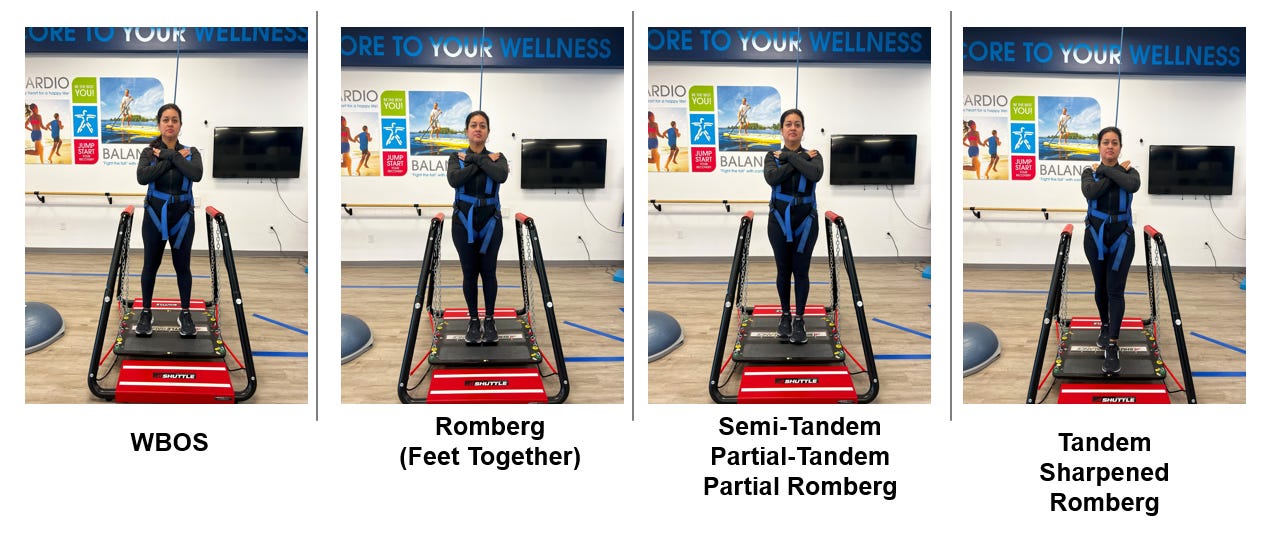

Romberg: Feet together, medial malleoli touching, calcaneus to calcaneus, and toes aligned. 'A stance of solidarity, where each foot mirrors the other in perfect symmetry.' This test (sometimes misspelled as 'Rhomberg'), named after German neurologist Moritz Heinrich Romberg (1795-1873), has been a cornerstone of neurological examination since the 19th century. Romberg, a pioneer in the study of tabes dorsalis (a condition affecting the spinal cord), observed that patients with this condition exhibited increased sway and instability when their eyes were closed while standing with their feet together. This observation led to the development of the Romberg Test, a simple yet powerful tool for assessing proprioception and balance.

Tandem (or Sharpened Romberg): A stance of challenge, where one-foot ventures forward, heel touching the toes of its steadfast companion. 'Calcaneus to hallux, a position demanding precision and control.' This variation, often called the Sharpened Romberg Test, increases the challenge to postural stability by reducing the base of support and requiring more precise control of body sway. While the exact origins of the term "Sharpened Romberg" are less clear, it likely emerged within clinical practice to emphasize the increased difficulty of this stance compared to the standard Romberg.

These two stances, the Romberg (feet together) and the Sharpened Romberg (or tandem), represent the bedrock of balance assessment. They are the anchors of our balance lexicon, the undisputed bookends of our stance vocabulary. But what lies between? What terminology navigates the territory between these two extremes?

Herein lies the 'partial' 'semi' or 'midstance' problems. A semantic swamp where clarity falters and consistency fades, highlighting the urgent need for standardized definitions.

Where Did Partial and Semi Come From?

The terms partial and semi have emerged over time as clinicians sought to describe variations in stance width between the extremes of Romberg and tandem. Unfortunately, these terms' lack of standardized definitions has led to the current confusion.

'Partial Romberg': This term likely arose from the need to describe stances where the feet were not fully together (Romberg) or heel-to-toe (tandem). However, the term remains ambiguous without specific guidelines on how "partial" the stance should be.

'Semi-tandem/Partial-Tandem': While intending to convey a stance "halfway" between Romberg and tandem, this term adds another layer of confusion. Does it genuinely mean exactly halfway? Or something closer to tandem? Its lack of a clear definition makes it problematic. Interestingly, the terms 'semi' and 'partial' share a common linguistic ancestry, both hinting at a state of incompleteness. However, this shared meaning doesn't resolve the ambiguity in balance stance terminology. While semi' might suggest the halfway point, 'partial' can encompass a broader range of positions, highlighting the need for precise descriptors.

The Need for Precision

Imagine this scenario: you're reviewing a patient's chart and encounter a perplexing array of descriptions: 'partial tandem,' then 'partial Romberg,' followed by 'semi-tandem.' What image does this conjure in your mind? Is it a narrow, wide, or something in between? The ambiguity overshadows the assessment, hindering accurate interpretation and consistent treatment planning. For instance, misinterpreting a 'partial Romberg' as a 'partial tandem' could lead to incorrect conclusions about a patient's balance, highlighting the potential consequences of imprecise balance assessment terminology.

Just as the elbow marks the midpoint between the arm and forearm, and the knee separates the thigh from the leg, we need a clear demarcation, a linguistic landmark, to guide us through the 'partial' territory.

This quest for clarity is not merely an academic exercise. It's about ensuring that our assessments are accurate, our communication is precise, and our patients receive the best possible care.

What the Romberg Test Tells Us

In its original clinical context, it's crucial to understand that the Romberg Test is primarily a test of proprioception – the body's awareness of its position in space. It helps differentiate between sensory ataxia (imbalance due to impaired proprioception) and cerebellar ataxia (imbalance due to cerebellar dysfunction).

A positive Romberg Test (increased sway with eyes closed) suggests a sensory component to the imbalance. However, it does NOT necessarily indicate brain damage or impairment. Many factors can contribute to a positive Romberg, including:

Inner ear problems

Peripheral neuropathy

Spinal cord compression

Certain medications

Normal aging

It's essential to interpret the Romberg Test within the context of a comprehensive examination and consider other factors contributing to balance difficulties.

The 'Partial' Solution

While eradicating 'partial' from our vocabulary might be unrealistic, we can improve its precision and consistency. Here's how:

1. Define the Extremes:

Start by clearly defining the two ends of the balance stance spectrum:

Romberg: Feet together, medial malleoli touching.

Tandem (or Sharpened Romberg): Heel-to-toe, with the front foot's heel touching the back foot's toes.

2. 'Partial' as a Continuum:

Emphasize that 'partial Romberg' and 'partial tandem' represent points along this continuum, NOT distinct categories.

3. Precision is Key:

Always, always, always include precise descriptors when using 'partial': Distance between feet: Measured in inches or centimeters.

Alignment of heels and toes: Are they aligned, offset, or staggered?

Specific foot placement: 'Heels touching, toes 2 inches apart,' 'Left foot slightly ahead of the right.'

4. Show, Don't Just Tell:

Use visual aids (photos, diagrams) to describe the exact foot position.

5. Function Over Form:

Connect the stance description to the purpose of the assessment or treatment. 'To challenge mediolateral stability, the patient was positioned in a partial Romberg stance with feet 3 inches apart.'

'To improve anterior-posterior control, a partial tandem stance with the left foot slightly ahead was used.'

A Call for Collective Clarity

Changing ingrained habits takes a collective effort. I urge all vestibular professionals to:

Embrace precision: Consciously adopt precise descriptors whenever using 'semi-tandem,' 'partial Romberg,' or 'partial tandem.'

Educate and advocate: Spread the word about the importance of clear communication in balance assessment. Encourage colleagues, students, and professional organizations to adopt standardized language.

By embracing a more precise and consistent approach to describing balanced stances, we can elevate the quality of our assessments, improve communication, and ultimately enhance the care we provide to our patients.

Let's end the 'partial' confusion and step towards a future of clarity and consistency in vestibular rehabilitation.